You hear the terms “status” and “reputation” bandied about endlessly. Consultants nod wisely, founders tweet buzzwords, and most of them treat the words like interchangeable synonyms. They’re not. These are different beasts entirely, different forms of social judgment that audiences render about organizations, and they address different questions an evaluator might have.

The Cult of Status

Think of status as your social standing. It’s less about what you do and more about who you are in the eyes of a relevant social group. Where did this idea come from? Sociologists, mostly, back to the OG Weber. Status doesn’t necessarily require you to prove your worth over and over; it often stems from your position. Are you part of the right club? Did you go to the right school? Do you associate with the right people? These affiliations, these positions, confer status… and especially early affiliations.

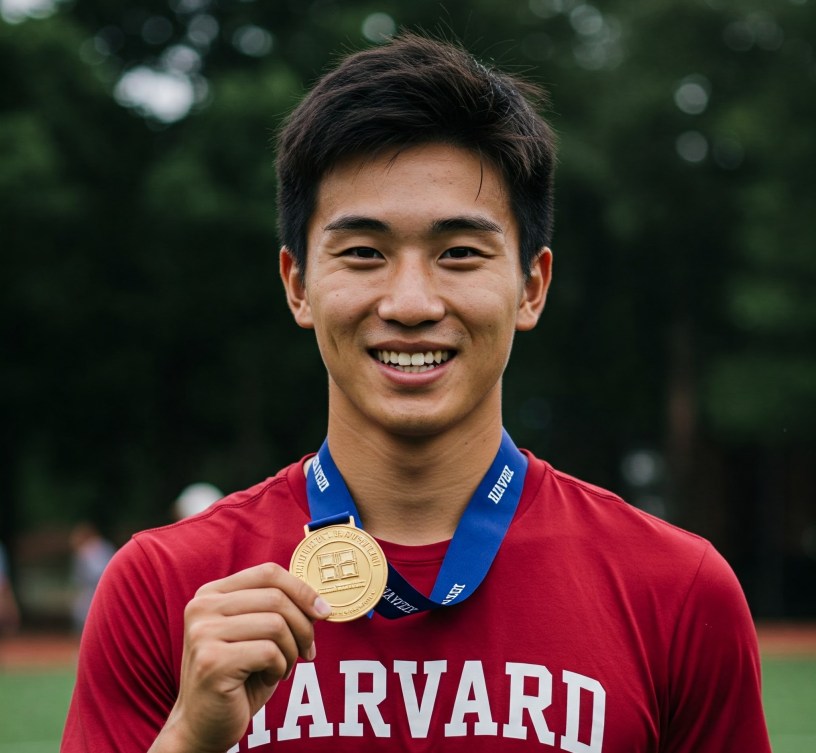

High status screams “quality!” even if the actual quality is hard to verify. Think of those fancy art galleries, or certain universities (starts with an “H” and ends with a “arvard”), or that one investment bank everyone claims is the best (whether they can explain why or not). The quality link might be tenuous, even based on superstitious learning effects. But once an organization or individual has it, the halo effect is real. High-status actors get preferential treatment. They attract better partners, talent, and resources, sometimes at a lower cost, because people want to bask in the reflected glory. It’s a self-confirming cycle, a virtuous (or vicious, depending on where you sit) feedback loop.

Status often operates on an ordinal scale; it’s about ranking within a group of similar entities. You’re higher or lower than someone else. It can even be categorical – you’re either in the high-status group or you’re not, with mechanisms of social closure preventing easy entry, even if you meet the basic performance criteria. And getting that spot? It’s often a struggle, negotiated behaviorally with other actors. Status can also be conferred instantly, sometimes unearned, based on shifts in context or sudden recognition. If your organization suddenly gets a prestigious award or a key affiliation, bam, instant status bump. Losing status, by the way, is often felt more keenly than gaining it. It’s about where you sit on the totem pole, and everyone else agreeing (inter-subjectively) on that position.

The Report Card of Reputation

Reputation, on the other hand, is the economist’s child. It’s built. Brick by brick, transaction by transaction. It’s derived from your past actions and consistent performance. When an evaluator makes a reputation judgment, they’re asking: “How will this organization perform/behave in the future relative to others in the set?”. They’re looking at the track record, the actual outcomes.

This is where the rubber meets the road, where quality isn’t just assumed but is ideally objectively observable, at least after the fact. Think of the auto industry: winning races proves your cars are fast and reliable. Or a bank’s history of managing funds. Customers use reputation, this summary of past performance, to predict future behavior, especially when they can’t fully assess quality upfront.

Reputation is fundamentally about comparison. It differentiates firms based on their demonstrated ability to deliver value. It’s less about belonging to a category (though that can play a role in initial screening) and more about where you stand when measured against specific, relevant attributes compared to your peers. Building a good reputation requires stakeholders to conduct “due diligence,” scrutinizing the organization’s features, processes, and outcomes. High economic stakes for the evaluator often prompt this deeper dive into reputation rather than relying on simpler status cues. It’s tied to an economic logic; it’s about the perceived ability to create value.

Why the Confusion Kills Your Strategy

So, status is about position and conferred perception, often categorical. Reputation is about performance history and earned validation, often more continuous and comparative. Status signals quality, while reputation is ideally built on demonstrated quality. Status is largely social, reputation is primarily economic. Status is homogenizing within a group, reputation is differentiating.

Why do people mix them up? Because they can be correlated. Performing well can certainly help you gain status, and high status can provide the resources to perform well consistently, reinforcing a positive reputation. But they are distinct processes. Measuring subjective perceptions, like general media coverage or survey results, often captures a blend of the two. If you want to truly separate them, you need more granular data – looking at specific transactions, comparing products where only the producer’s identity varies, and understanding the evaluator’s motivations and context.

For managers, this difference is crucial because the strategy you use to manage one won’t necessarily work for the other. Trying to win over regulators concerned with societal benefit, by focusing solely on climbing status rankings among peers, might be a waste of effort. Trying to attract savvy investors who perform thorough due diligence on performance history (reputation judgment), by simply securing a high-status affiliation, won’t fly. You need to understand which judgment your key stakeholders are making, given the context and their own needs and limitations. Are they looking for pedigree (status) or proof (reputation)? Are they swayed by who you know or what you’ve done? Answering these questions will help you to decide whether status or reputation are central to a strategy.

Bibliography

Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151-179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

George, G., Dahlander, L., Graffin, S. D., & Sim, S. (2016). Reputation and status: Expanding the role of social evaluations in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4001

Sorenson, O. (2014). Status and reputation: Synonyms or separate concepts?. Strategic Organization, 12(1), 62-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013513219

Discover more from Prefrontal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.