You think you’re in control? You think your decisions about money, about who to trust, about whether to take a risk, are purely rational calculations made in the pristine halls of your prefrontal cortex? Your brain, bless its complex little heart, might have other ideas. And some of those ideas come straight from the chemical soup sloshing around inside your skull.

There is a messy intersection of neuroeconomics and pharmacology. This field isn’t just asking what decisions you make, or why you make them in some abstract, theoretical sense. It’s starting to ask: What specific biological mechanisms, what molecules, what chemical signals, are actually pulling the strings? It’s about understanding the neural hardware and the chemical processes that underlie everything from buying a lottery ticket to deciding if you trust a stranger.

For decades, economics largely ignored the biological reality of the decision-maker. Neoclassical theory, for instance, operated on the idea of ‘as if’ rationality. You behave as if you’re maximizing some abstract utility function, they argued, and whether you actually do that internally is irrelevant. This approach had power but hit walls when real human behavior consistently violated its simple axioms – paradoxes popped up, and the clean models didn’t quite map onto messy reality. Behavioral economics stepped in, saying, “Hey, maybe psychology matters!”. And now, neuroeconomics is taking it a step further, saying, “Maybe the actual brain wiring and chemistry matters, and can help us figure out how and why those violations happen”.

Pharmacology is one of the sharpest tools in the neuroeconomic shed for this very reason. It’s not just about correlating brain activity with decisions; it’s about causally manipulating the system and seeing what breaks, or more interestingly, what changes.

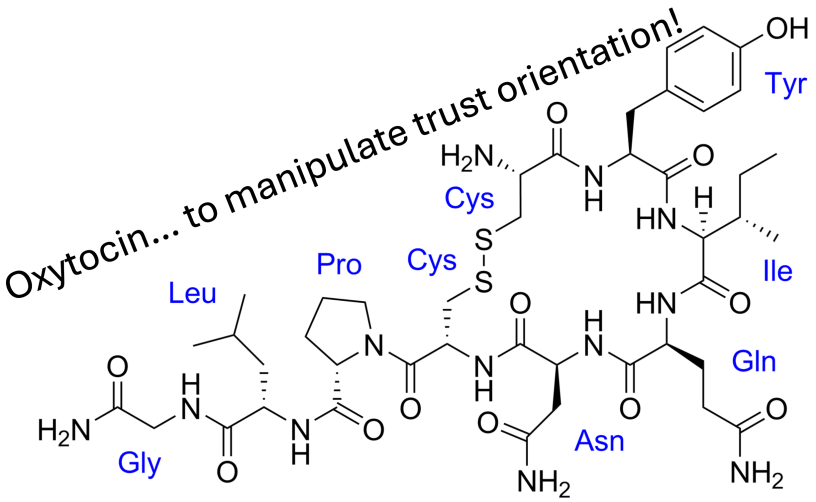

Oxytocin: The Trust Hormone? Maybe.

Let’s talk about trust. It’s fundamental to economic exchange and social interaction. If you don’t trust the other person to pay you back, you don’t lend them money. Simple, right? But what if we could pump some chemicals into the equation?

One major finding highlighted in the sources involves oxytocin, a neuropeptide. Researchers designed an experiment using a “trust game” where one person (the investor) decides how much money to send to another person (the trustee), knowing the amount sent will be tripled, and the trustee then decides how much of the increased sum to send back.

Here’s where the chemistry comes in. Before playing, some investors received an intranasal dose of oxytocin, while others got a placebo. The result? Investors who got oxytocin sent significantly more money to the trustees compared to the placebo group.

Now, what does this tell us? It’s not just that oxytocin makes you generally risk-seeking, or just makes you nicer overall. The study included control conditions. Oxytocin didn’t change how trustees behaved (they didn’t send back more). It also didn’t make investors take more risks in a different game that involved pure financial risk, not interaction with another human.

The key insight? This neuropeptide seemed to specifically increase the investors’ willingness to accept the risk associated with interacting with another person. It suggests a neurobiological basis for distinguishing between risks involving people versus risks involving just random chance. It’s a direct line from a specific chemical to a specific, complex social and economic behavior: trust.

Beyond Trust: Interrupting the System

Another way to probe the causal role of brain mechanisms (though not strictly pharmacology in this case, but related to manipulating the system) is to temporarily disrupt neural activity. The sources point to studies using non-invasive methods to mess with specific brain regions.

Consider the “ultimatum game,” where one player proposes splitting a sum of money, and the other player can either accept (and they both get the proposed split) or reject (and neither player gets anything). Rationally, the second player should accept any non-zero offer, because getting something is better than nothing. But humans often reject low, unfair offers – it’s a demonstration of social preferences and fairness concerns.

When researchers non-invasively disrupted activity in a specific part of the frontal cortex of the player responding to the offer, something fascinating happened: these players were significantly more likely to accept unfair offers. Crucially, their judgment about whether the offer was fair or not wasn’t changed; they still knew it was unfair. The disruption seemed to affect the mechanism that translated that fairness judgment into the decision to reject.

This shows a causal link between specific neural activity and complex social behavior. It also highlights a potential dissociation: the brain processes fairness in one area, but a different area might be critical for enforcing that fairness judgment through actual choice. While not a drug study, it underscores the same principle: messing with the biological machinery changes the economic/social outcome.

The Takeaway

So, what’s the point? The point is that our economic and social decisions, the ones that economists modeled with abstract utility functions and behavioral economists explored with clever experiments, are ultimately implemented by biological hardware and software. Pharmacology, by introducing or blocking specific chemical signals, allows us to see how this machinery works and, more importantly, how specific components causally influence behavior.

The simple models of rational choice are powerful tools for analysis, but they are approximations. Real humans are messy, influenced by everything from context to emotion to, yes, the levels of various chemicals in their brains. Understanding these biological underpinnings, as neuroeconomics and its pharmacological tools are starting to do, isn’t just academic curiosity. It’s foundational to truly understanding how decisions are made, why people deviate from predictions, and perhaps eventually, how to build better models or even design better policies. Your choices aren’t made in a vacuum; they’re made in a body, with a brain, influenced by chemistry you’re only beginning to understand.

Bibliography

Glimcher, P.W., & Fehr, E. (2014). NeuroEconomics: Decision making and the brain, 2nd Edition. New York, Academic Press,

Discover more from Prefrontal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.