Every student cracking open an intro neuroscience or psych textbook knows the story. Phineas Gage, the capable foreman, struck by a massive iron bar through his head. Miraculously, he survives. But his personality flips. He becomes “no longer Gage”, an irreverent, fitful, profane drifter. A perfect, tragic tale illustrating how frontal lobe damage nukes your character. It’s iconic, near-legendary, practically holds mythical status. Case closed, right?

The Myth Machine(?)

The key accounts of Gage’s case come from Dr. John Martyn Harlow, who treated Gage immediately after the accident, and Dr. Henry Bigelow, who examined him about a year later. Harlow published reports in 1848 and, critically, a follow-up in 1868, years after Gage’s death. It’s in this later report that Harlow famously described Gage as “radically changed,” so much so that friends said he was “no longer Gage”. He noted Gage became fitful, irreverent, indulged in gross profanity, showed little deference, was impatient of restraint, and vacillated between plans. This two-paragraph description became the foundation for the “psychopathic drifter” image.

Textbooks ran with it. Across dozens of introductory psychology texts over the years, the story gets repeated, often with embellishments not found in the primary sources. For instance, claims that Gage never worked again, became a vagrant, toured the country exhibiting himself for money, or even that he lived with the iron still in his head. These are outright fabrications or wild exaggerations. Why? Because it makes for a hell of a story. A man surviving a crowbar through the head and turning into a monster? That sells.

The Real Gage

Actually, we know surprisingly little for sure about Gage’s behavior after his initial recovery period. Harlow’s famous description covers a few hundred words, and Bigelow, who observed Gage a year later, surprisingly reported him as “quite recovered in his faculties of body and mind,” finding him “shrewd and intelligent”. Bigelow’s assessment is often downplayed or ignored in the popular telling.

More importantly, evidence exists that Phineas Gage did function after the accident. He traveled extensively, going to Boston, around New England, and even spent nearly seven years in Valparaiso, Chile, working as a stagecoach driver. Driving a stagecoach with six horses requires significant cognitive, motor, and interpersonal skills. This isn’t the work of a complete write-off, certainly not a witless psychopath.

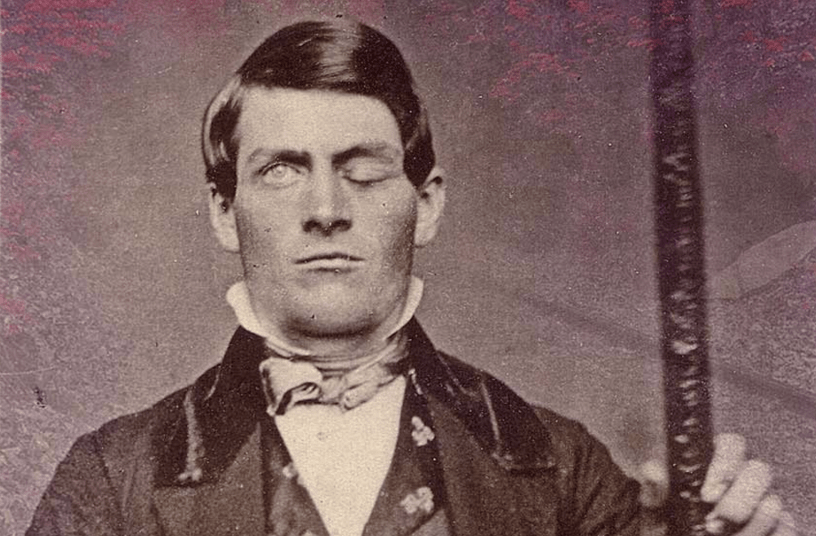

Then there’s the visual evidence. Until recently, no verified photos of Gage were known. But the discovery of daguerreotypes, particularly one published in 2009, shows a well-dressed, self-assured, and seemingly confident man holding his tamping iron. This image directly contradicts the widespread depiction of him as a disheveled vagrant. While you can’t diagnose personality from a photo, this daguerreotype strongly supports the idea that Gage made a substantial psychosocial recovery, or at least adapted far better than the myth allows.

The Science vs. The Narrative

Modern science has tried to refine the picture. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of Gage’s skull, researchers have created 3D reconstructions to map the likely path of the iron and the extent of brain damage. Studies suggest the injury was primarily limited to the left frontal lobe and caused significant white matter damage, including pathways like the uncinate fasciculus and cingulum. This damage could indeed explain behavioral issues.

However, even these sophisticated analyses are based on a skull from over a century ago, without the original brain tissue or a recorded autopsy. They are estimates. The reality is messy: the exact extent of damage, including secondary effects like hemorrhaging or infection, is difficult to know precisely. Brain structure and location also vary between individuals. Basing definitive statements about brain function on this single, complex, historical case is problematic.

The Real Takeaway

It’s not the simple, clean narrative about frontal lobes controlling personality that fills textbooks. The real lesson of Phineas Gage is about the power of narratives, how they get distorted, and how hard it is to correct the record, even with new evidence. Could it be that many modern commentators exaggerate Gage’s personality change, retrospectively fitting the story to our current understanding of the frontal cortex.

Gage’s story should teach students not just about the brain, but about the history of science, the fallibility of accepted wisdom, and the importance of scrutinizing primary sources. It’s a testament to brain resilience and adaptation (neuroplasticity, if you want the fancy term). It highlights the complexity of brain-behavior relationships, which can’t be reduced to a single, sensational case study.

Phineas Gage was not just a damaged brain or a character flipping from saint to sinner. He was a man who survived an unimaginable trauma, was profoundly changed, yes, but likely found a way to live and work for over a decade.

Bibliography

Griggs, R. A. (2015). Coverage of the Phineas Gage story in introductory psychology textbooks: was Gage no longer Gage?. Teaching of Psychology, 42(3), 195-202. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315587614

Kotowicz, Z. (2007). The strange case of Phineas Gage. History of the Human Sciences, 20(1), 115-131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695106075178

Ratiu, P., Talos, I. F., Haker, S., Lieberman, D., & Everett, P. (2004). The tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered. Journal of neurotrauma, 21(5), 637-643. https://doi.org/10.1089/089771504774129964

Shelley, B. P. (2016). Footprints of phineas gage: Historical beginnings on the origins of brain and behavior and the birth of cerebral localizationism. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 4(2), 280-286. DOI: 10.4103/2321-4848.196182

Discover more from Prefrontal

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.